Legislating Architecture

Most architects choose to speak of their work as acts of deliberate authorship and the resulting manifestations of individual creativity. Few make reference to the zoning restrictions or building code conformance that determined the project to be of a certain size or construction. A similar commentary applies to the clever condominium developer

purporting acts of altruistic sustainability by neglecting to disclose that the bicycle parking, electric-vehicle charging or green roof of their building was required by municipal by-law, but that is another story... It is an ignorant fiction to suggest today that architects control the design of buildings. A more honest description might be to describe architects as the manipulators of regulations, codes and standards into built form.

Arno Brandlhuber is an architect that has frolicked since the 1990’s in the legislative mud of building codes and municipal zoning by-laws in Germany. In 2016, Brandlhuber co-edited the 225th edition of ARCH+ magazine, entitled ‘Legislating Architecture’ to explore how architecture is shaped by societal regulatory systems and law. The opening essay asks “can architects play a role in creating the legislative framework of their own practice? Can we create a self-aware architecture that challenges the status quo by being a catalyst to renegotiate our legislative conditions?” It is this question that underpins the work of The Second Egress, the idea that architects should actively question and contribute to the rules we work with.

Arno Brandlhuber is an architect that has frolicked since the 1990’s in the legislative mud of building codes and municipal zoning by-laws in Germany. In 2016, Brandlhuber co-edited the 225th edition of ARCH+ magazine, entitled ‘Legislating Architecture’ to explore how architecture is shaped by societal regulatory systems and law. The opening essay asks “can architects play a role in creating the legislative framework of their own practice? Can we create a self-aware architecture that challenges the status quo by being a catalyst to renegotiate our legislative conditions?” It is this question that underpins the work of The Second Egress, the idea that architects should actively question and contribute to the rules we work with.

“In architecture, countless constraints and conditions lead to the design. The specific constraints and conditions imposed by the word are known to planners and designers as building law, zoning law or building code and are accepted, or at best interpreted, as such. Can these constraints and conditions also be understood as tools of design rather than as obstacles? Can planners and designers influence the definition of these constraints and conditions instead of being mere executors?”

- Brandlhuber, Arno and Roth, Christopher. (2017).The Property Drama. Film.

- Brandlhuber, Arno and Roth, Christopher. (2017).The Property Drama. Film.

“Many architects do not particularly like to talk about economic and political outline conditions which, in their opinion, restrict their artistic freedom, or in the worst case, are seen as attacking the autonomy of the discipline of architecture. Other architects, however, make extensive use of rules, restrictions and opposition. For them deriving a concept from the outline conditions can, at times, represent the design act per se – the concept of a diagrammatic architecture that allows itself be used as a multi-purpose design weapon in each and every situation, so to speak.”

- Müller, Mathias and Niggli, Daniel. (2012).

Learning from Tokyo, EM2N.

Learning from Tokyo, EM2N.

"Architecture during the last two centuries … is employed more and more as a preventive measure; an agency for peace, security and segregation which, by its very nature, limits the horizon of experience – reducing noise-transmission, differentiating movement patterns, suppressing smells, … veiling embarrassment, closeting indecency and abolishing the unnecessary; incidentally reducing daily life to a private shadow-play. But on the other side of this definition, there is surely another kind of architecture that would seek to give full play to the things that have been so carefully masked by its antitype; an architecture arising out of the deep fascination that draws people towards others; an architecture that recognizes passion, carnality and sociality."

- Evans, Robin (1997). “Figures, Doors and Passages.”

Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, London.

Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, London.

“Architects have essentially been neutered since the 1950’s!”

- Prof. Andrew King, referring to practice in North America. (2021).

2.56m

Arno Brandlhuber & Bernd Kniess + Uwe Schnatz (1997)

Eigelstein 115, 50668 Köln, Germany

Eigelstein 115, 50668 Köln, Germany

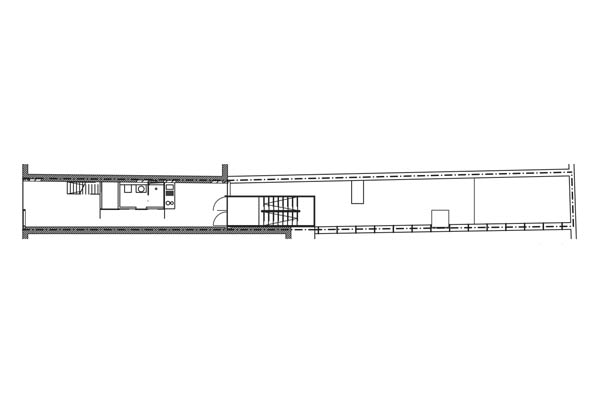

“Inserted in an extremely narrow gap—just 2.56 meters wide—the project is less a house in the classical four-walls-and-one-roof sense but an infill for Cologne’s city center. The office and apartment building uses the existing party walls of the neighboring houses by inserting the concrete floor slabs directly into them, which allows for maximized use of the limited space. At ground level, a narrow corridor passes through the building into the rear courtyard, connecting the sidewalk with the exterior staircase at the back of the building. Relocating the vertical circulation to the outside not only increases the use of interior space but also allows for separate use by the apartment tenants. The one-room units have no partition walls. Instead, the core, comprised of the bathroom and storage space, divides the open floor into zones and permits minimum spatial separation. The apartments are open to the east and west sides of the building. With fully glazed facades this provides an unexpectedly spacious feeling inside which is continued on the roof terrace.”

“In addition to the specific construction requirements of the narrow site, the building’s shape derives primarily from the legal situation. The German building code required each building in a block to be an independent construction. This law countered the owner’s arrangement with his neighbors, who asked him to maintain the shared party walls as part of the new structure. This condition was later adopted by the German building code as the so-called Verweisbaulast (reference construction encumbrances). The new code allowed for the use of adjacent party walls in new constructions, citing 2.56 as its legal precedent.”

Brunnenstrasse 9

Brandlhuber+ (2010)Brunnenstrasse 9, 10119 Berlin-Mitte, Germany

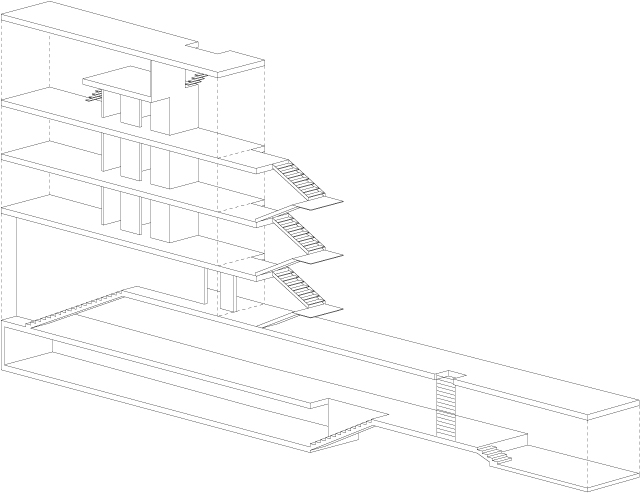

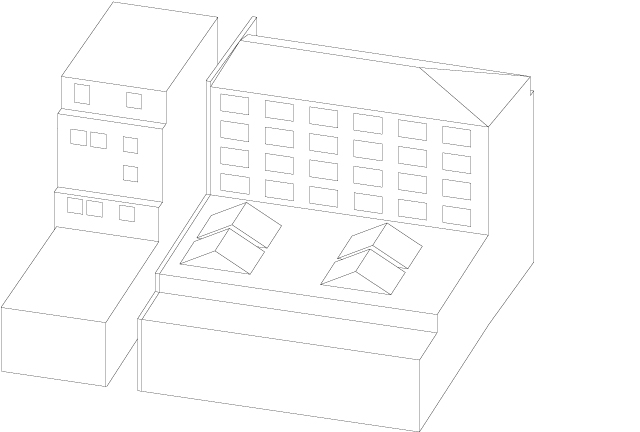

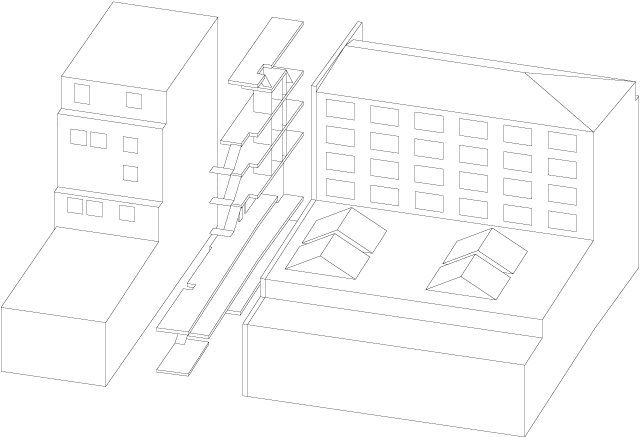

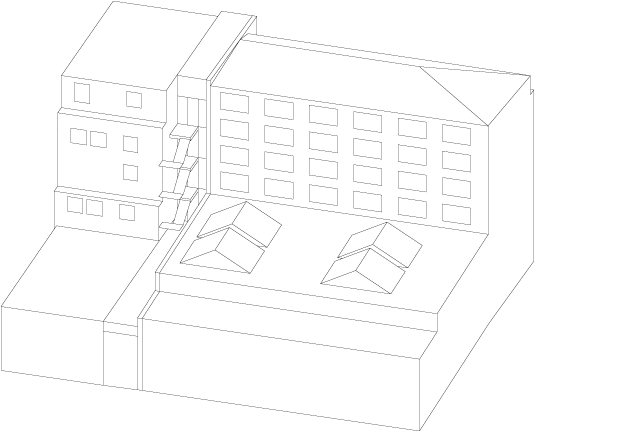

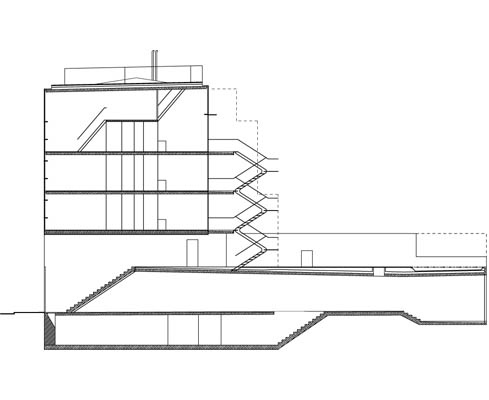

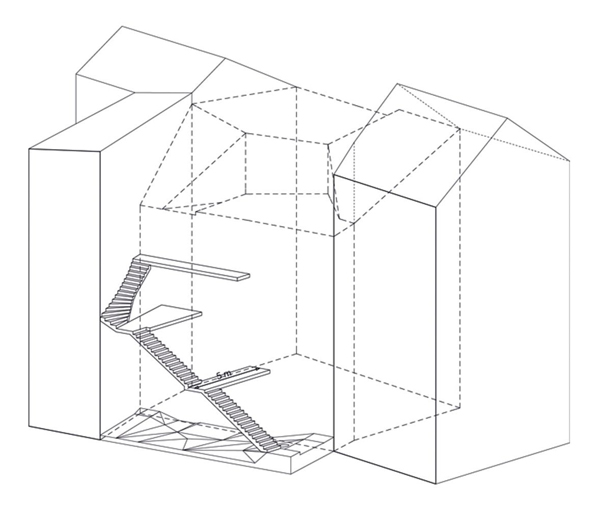

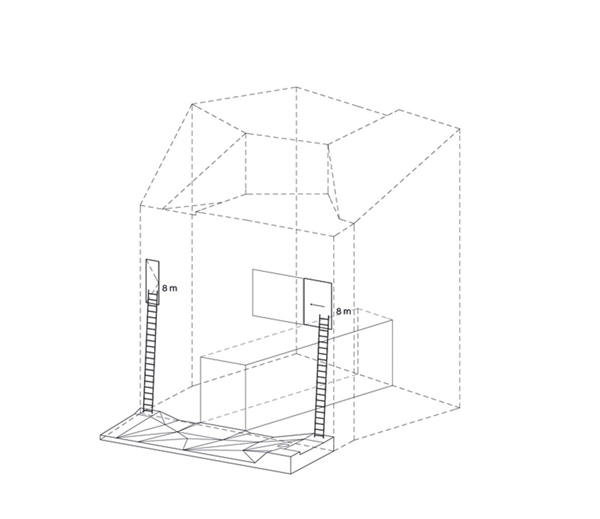

“The concrete core, reduced to a minimum, houses the bathrooms and the elevator. It directly connects the different units to the street level via an entrance located in the public passageway. Apart from this central core, there is no other physical connection between the single units. The only way to circulate between them is either through elevator access or the external staircase attached to the rear façade. This exterior circulation layer is offset five meters from the back façade in accordance with the building code and fire regulations. The need for an interior stair is eliminated by shifting the staircase outside, which permits maximum spatial efficiency and complete independence for the users. The platforms connecting the exterior staircase also function well as terraces and public space for the residents. As the tram wires prevent firefighters from using extendible ladders on the street side, a second entrance had to be installed at the rear. In order to comply with regulations for the second fire escape —via the windows— the courtyard ground was raised 72cm on one side and 36cm on the other to match the maximum length of the fire brigade’s 8-metre ladder.”

Brandlhuber, Arno. (2018). Brunnenstrasse. Atlas of Places.

https://www.atlasofplaces.com/architecture/brunnenstrasse/

https://www.atlasofplaces.com/architecture/brunnenstrasse/