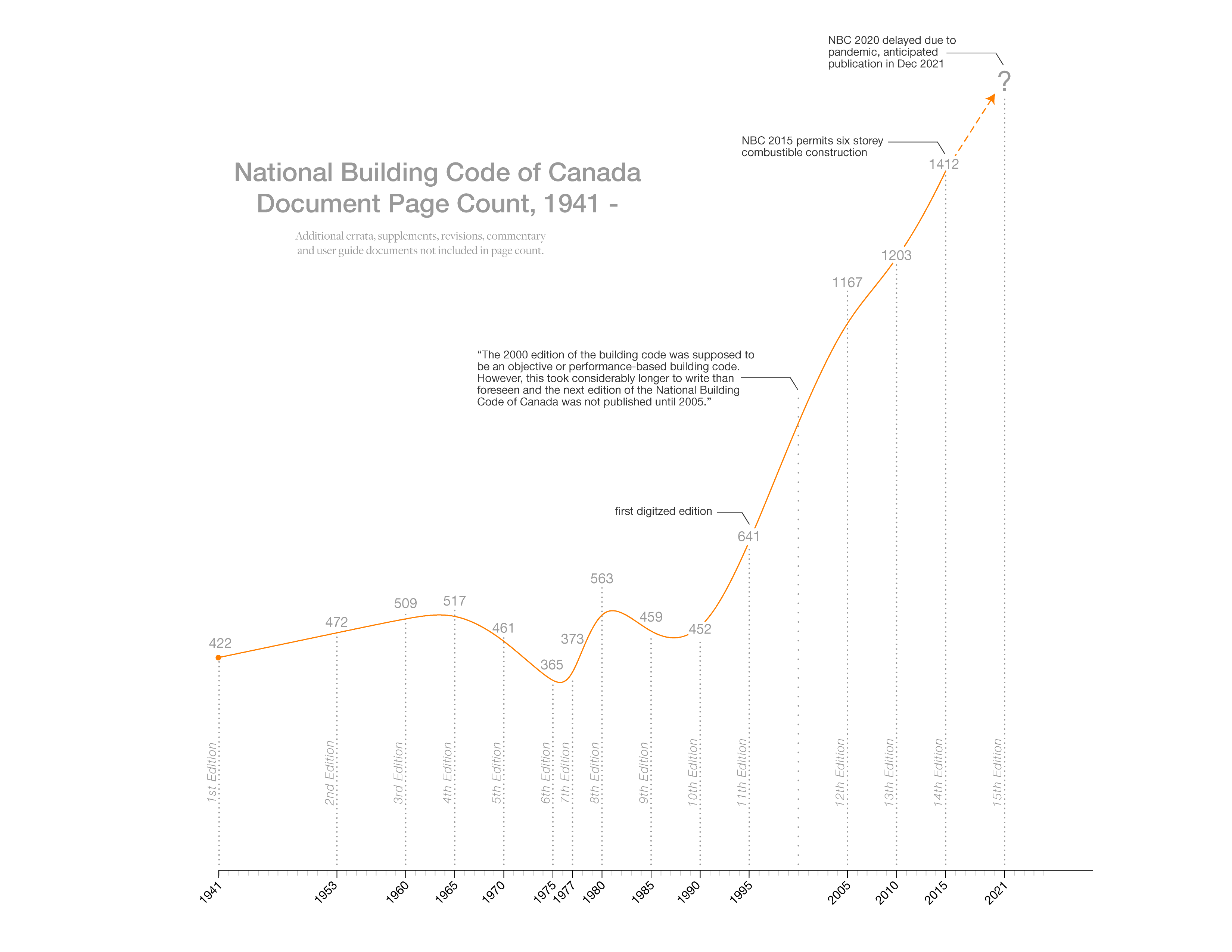

National Building Code

“In the broadest sense, building regulations develop from contingency to contingency. Each one represents an emergency measure taken with very little or no study. As the emergency recedes, the regulation tends to form part of traditional practice. It is added to the pile, which grows and grows.

Progress towards better regulations in this country will be speeded when we have an understanding of the history of the regulations which are now enforced.”

- R.S. Ferguson, Head of Building Standards Section (1960’s). National Research Council of Canada.

An understanding of the history of the National Building Code is critical to examining the technical rationale for the regulations today.

In 2008, the B.C. Office of Housing and Construction Standards hired Senez Reed Calder Fire Engineering Inc. to prepare a report on the historical origins for some of the requirements in the National Building Code of Canada. In particular, the report is a deep-dive into the rationale for the height and area limits of combustible construction: The report documents the history of the building code in Canada and accounts for the influence of regulations in the US and disastrous conflagrations across North American cities at the turn of the century.

Extracts from Calder, K et al. (2008). A Historical Perspective on Building Heights and Areas in the British Columbia Building Code

In 2008, the B.C. Office of Housing and Construction Standards hired Senez Reed Calder Fire Engineering Inc. to prepare a report on the historical origins for some of the requirements in the National Building Code of Canada. In particular, the report is a deep-dive into the rationale for the height and area limits of combustible construction: The report documents the history of the building code in Canada and accounts for the influence of regulations in the US and disastrous conflagrations across North American cities at the turn of the century.

Extracts from Calder, K et al. (2008). A Historical Perspective on Building Heights and Areas in the British Columbia Building Code

“The first edition of Canada’s National Building Code was published in 1941 and was based on the US model codes available at that time. The development of the Canadian and US model codes originated out of a need to regulate construction on a national basis. Most of the requirements in both the Canadian and US building codes were developed based on large city regulations in existence at the time of their development, with the intention of limiting large catastrophic fire events such as conflagrations or fires with large life loss...”

“...Most of these requirements originated from the local codes that existed in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago and Baltimore. These were all cities in which large conflagrations had occurred, accelerating the development of local building regulations...”

“...The basis for the height and area limitations in the 2006 BCBC were developed nearly 100 years ago when city conflagration or large life loss were prominent considerations. The means for dealing with these risks, in part, was to limit the height and area of buildings to what the fire department of the time could reasonably handle. The statistical fire record has shown that the number of fires is decreasing, loss of life in fires has decreased, and the relationship of city-wide conflagrations to interior building design is not correlated in a reasonable way to building height and area. In summary, there is a lack of definition to correlate the building area and height to the overall construction, compartmentation, and fire and life safety systems...”

“...Building area and heights were based on a survey of fire services capabilities in the early 1900’s. During this era:

- Construction: The methods of construction were vastly different and methods of determining fire resistance of structures were in their infancy.

-

Compartmentation: The degree of building compartmentation that was factored into the reviews is not

representative of residential construction in today’s code.

-

Interior Finishes: Interior finishes were less controlled and flame-spread concepts were in their

infancy. Wood was a more predominant ceiling finish, whereas gypsum board is a

more common material for walls and ceilings in residences today.

-

Evacuation: Exiting, fire alarm systems, and evacuation plans were less regulated and less effective. Concepts on evacuation relative to building height were based on buildings with open or unprotected stairs and not fire separated stair shafts as

required by today's codes.

-

Behaviour: The behaviour of people during a fire had not been studied and was therefore not

understood.

-

Firefighting: To the extent that it exists today, fire services did not have breathing apparatus, fire

fighter’s stairs, aerial ladder trucks, addressable fire alarm systems, and floor plans.

Hence, the building area and height rationalization based on hose stream penetration is not representative of today's capabilities...”

History of the Single Exit Requirements in the National Building Code of Canada

The table below looks specifically at the history of the second egress provisions in the National Building Code of Canada. The first edition of the NBC in 1941 permitted up to three storeys of noncombustible construction to be served by a single exit, which was later decreased to two storeys and reduced floor areas.

Given the conclusions of the Senez Reed Calder report, the requirement for a second means of egress in the building code today may also be the result of pre-modern fire safety practices in the early 1900’s and remains engrained and unquestioned in the National Building Code today.

The table below looks specifically at the history of the second egress provisions in the National Building Code of Canada. The first edition of the NBC in 1941 permitted up to three storeys of noncombustible construction to be served by a single exit, which was later decreased to two storeys and reduced floor areas.

Given the conclusions of the Senez Reed Calder report, the requirement for a second means of egress in the building code today may also be the result of pre-modern fire safety practices in the early 1900’s and remains engrained and unquestioned in the National Building Code today.

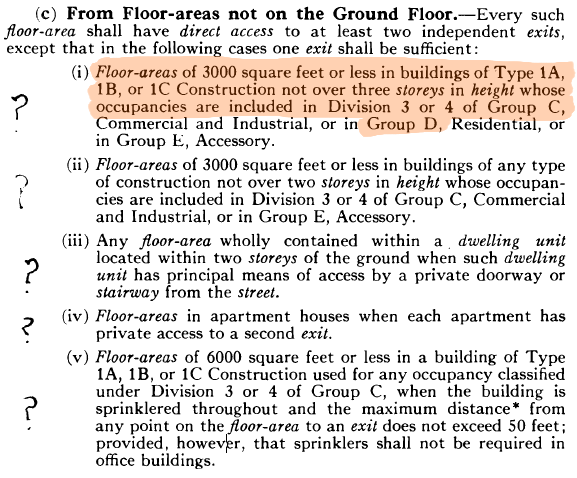

NBC 1941

The first edition of the building code permits up to three storeys of noncombustible construction to be served by a single exit.

The first edition of the building code permits up to three storeys of noncombustible construction to be served by a single exit.

Section 4.6.5 Number, Location and Width of Exits (pg 218)

(c) From Floor-areas not on the Ground Floor. - Every such floor-area shall have direct access to at least two independent exits, except that in the following cases one exit shall be sufficient:

(c) From Floor-areas not on the Ground Floor. - Every such floor-area shall have direct access to at least two independent exits, except that in the following cases one exit shall be sufficient:

(i) Floor-areas of 3,000 square feet or less in buildings of Type 1A, 1B or 1C Construction not over three storeys in height whose occupancies are included in Division 3 or 4 of Group C, Commercial and Industrial, or in Group D, Residential, or in Group E, Accessory.

Note: Type 1A, 1B or 1C Construction require noncombustible construction for all load-bearing elements.

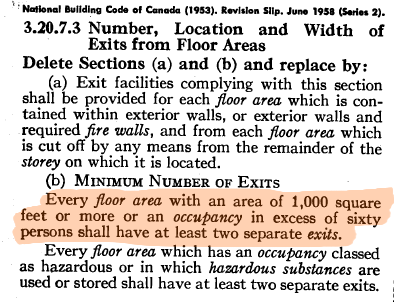

NBC 1953

The second edition of the building code introduces occupancy load limits for a single exit and restricts the maximum floor area from 3,000 down to 1,000 square feet.

The second edition of the building code introduces occupancy load limits for a single exit and restricts the maximum floor area from 3,000 down to 1,000 square feet.

3.20.7.3 Number, Location and Width of Exits from Floor Areas

(b) Minimum Number of Exits

Every floor area with an area of 1,000 square feet or more or an occupancy in excess of sixty persons shall have at least two separate exits.

(b) Minimum Number of Exits

Every floor area with an area of 1,000 square feet or more or an occupancy in excess of sixty persons shall have at least two separate exits.

NBC 1960

The third edition of the building code maintains the provisions of the 1953 code and outlines the principles for the design of means of egress, engraining these concepts in future development of the code.

The third edition of the building code maintains the provisions of the 1953 code and outlines the principles for the design of means of egress, engraining these concepts in future development of the code.

3.4.1 General Requirements for Means of Egress

Principle 1: Means of egress are of two kinds, exit and access to exits. Exits (such as stair towers) should be designed for the sole purpose of escape. The standards of design within any exit enclosure should be adequate to satisfy the extra hazards of escape under the severe conditions imposed by fire. In many cases the standards for access to exits must be less stringent than those for exits because the access is within a floor area and must serve the needs of everyday use and occupancy as well as escape. Where floor areas are divided into rooms served by corridors, such corridors, even though they are defined as “access”, should be regarded almost as an “exit.”

Principle 2: Means of egress, both access and exits, should be designed to increase in width as tributary population feeds into the main stream.

Principle 3: Means of egress should be designed so that the escape route is always in a direction away from any possible fire. This means, in theory, that for any position in a building which might be occupied, it should be possible to travel in two directions since it is unlikely that both will be cut off at once. Ideally, therefore, corridors should have exits at both ends. Practically, it is difficult to achieve this ideal within individual suites and it is less important to achieve it in some circumstances such as where an entire floor area is one office or under the control of one person or which is not indended for infirm persons or for sleeping. Under some circumstances, therefore, a reasonable length of dead end may be tolerated but only with the approval of the authority having jurisdiction and only when no other reasonable solution exists.

Principle 4: Exit safety in multistorey buildings is almost wholly dependent on the escape routes from any floor being fire separated from the other floors. This not only means that all exit stairs should be in fire-resistive shafts but that the doorways in such shafts should be closed off with fire doors. Even this is almost useless unless such doors are kept closed. Unless these construction practices are adhered to and the discipline of keeping doors closed is maintained, equivalent safety (ultimate safety is never possible) can only be achieved by the most complete sprinkler system and elaborate and expensive alarms.

Principle 1: Means of egress are of two kinds, exit and access to exits. Exits (such as stair towers) should be designed for the sole purpose of escape. The standards of design within any exit enclosure should be adequate to satisfy the extra hazards of escape under the severe conditions imposed by fire. In many cases the standards for access to exits must be less stringent than those for exits because the access is within a floor area and must serve the needs of everyday use and occupancy as well as escape. Where floor areas are divided into rooms served by corridors, such corridors, even though they are defined as “access”, should be regarded almost as an “exit.”

Principle 2: Means of egress, both access and exits, should be designed to increase in width as tributary population feeds into the main stream.

Principle 3: Means of egress should be designed so that the escape route is always in a direction away from any possible fire. This means, in theory, that for any position in a building which might be occupied, it should be possible to travel in two directions since it is unlikely that both will be cut off at once. Ideally, therefore, corridors should have exits at both ends. Practically, it is difficult to achieve this ideal within individual suites and it is less important to achieve it in some circumstances such as where an entire floor area is one office or under the control of one person or which is not indended for infirm persons or for sleeping. Under some circumstances, therefore, a reasonable length of dead end may be tolerated but only with the approval of the authority having jurisdiction and only when no other reasonable solution exists.

Principle 4: Exit safety in multistorey buildings is almost wholly dependent on the escape routes from any floor being fire separated from the other floors. This not only means that all exit stairs should be in fire-resistive shafts but that the doorways in such shafts should be closed off with fire doors. Even this is almost useless unless such doors are kept closed. Unless these construction practices are adhered to and the discipline of keeping doors closed is maintained, equivalent safety (ultimate safety is never possible) can only be achieved by the most complete sprinkler system and elaborate and expensive alarms.

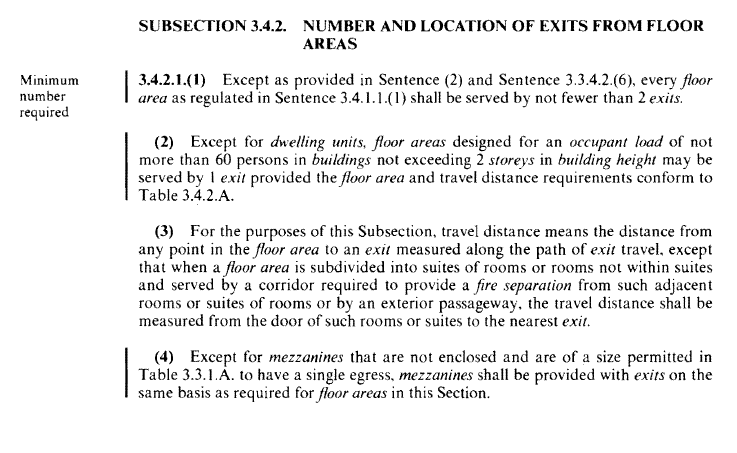

NBC 1977

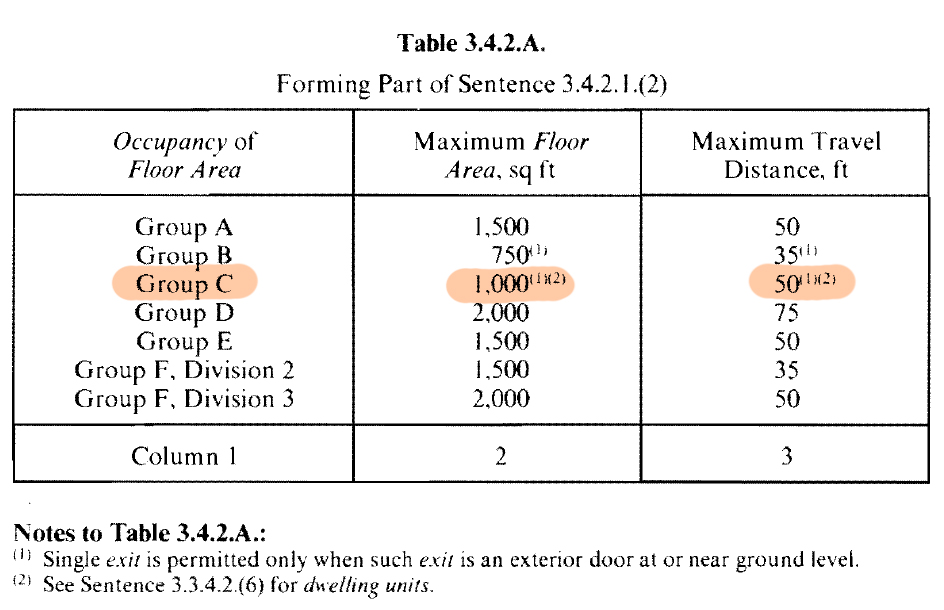

The seventh edition refers to travel distance requirements depending on the floor area occupancy category to determine if one exit is allowed.

The seventh edition refers to travel distance requirements depending on the floor area occupancy category to determine if one exit is allowed.

3.4.2. Number and Location of Exits from Floor Areas

(1) Except as provided in Sentence (2) and Sentence 3.3.4.2.(6), every floor area as regulated in Sentence 3.4.1.1.( 1) shall be served by not fewer than 2 exits.

(2) Except for dwelling units, floor areas designed for an occupant load of not more than 60 persons in buildings not exceeding 2 storeys in building height may be served by 1 exit provided the floor area and travel distance requirements conform to Table 3.4.2.A.

(1) Except as provided in Sentence (2) and Sentence 3.3.4.2.(6), every floor area as regulated in Sentence 3.4.1.1.( 1) shall be served by not fewer than 2 exits.

(2) Except for dwelling units, floor areas designed for an occupant load of not more than 60 persons in buildings not exceeding 2 storeys in building height may be served by 1 exit provided the floor area and travel distance requirements conform to Table 3.4.2.A.

NBC 1980

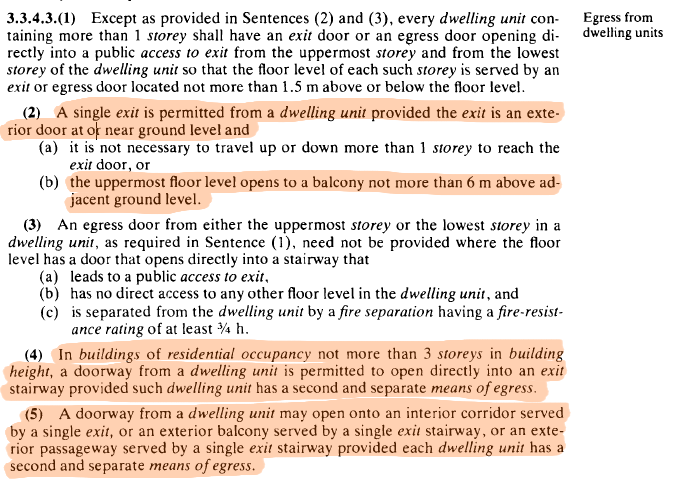

The eight edition permits the construction of three-storey townhouses accessed directly from the exterior, also clarifying that dwelling units in buildings up to three storeys can open directly into an exit stairway. Travel distances and floor areas are converted from imperial to metric units.

The eight edition permits the construction of three-storey townhouses accessed directly from the exterior, also clarifying that dwelling units in buildings up to three storeys can open directly into an exit stairway. Travel distances and floor areas are converted from imperial to metric units.

3.3. Safety Requirements within Floor Areas

3.3.4 Residential Occupancy

3.3.4.3.(1) Except as provided in Sentences (2) and (3), every dwelling unit containing more than 1 storey shall have an exit door or an egress door opening directly into a public access to exit from the uppermost storey and from the lowest storey of the dwelling unit so that the floor level of each such storey is served by an exit or egress door located not more than 1.5 m above or below the floor level.

(2) A single exit is permitted from a dwelling unit provided the exit is an exterior door at or near ground level and (a) it is not necessary to travel up or down more than 1 storey to reach the exit door, or (b) the uppermost floor level opens to a balcony not more than 6 m above adjacent ground level.

(4) In buildings of residential occupancy not more than 3 storeys in building height, a doorway from a dwelling unit is permitted to open directly into an exit stairway provided such dwelling unit has a second and separate means of egress.

(5) A doorway from a dwelling unit may open onto an interior corridor served by a single exit, or an exterior balcony served by a single exit stairway, or an exterior passageway served by a single exit stairway provided each dwelling unit has a second and separate means of egress.

3.3.4 Residential Occupancy

3.3.4.3.(1) Except as provided in Sentences (2) and (3), every dwelling unit containing more than 1 storey shall have an exit door or an egress door opening directly into a public access to exit from the uppermost storey and from the lowest storey of the dwelling unit so that the floor level of each such storey is served by an exit or egress door located not more than 1.5 m above or below the floor level.

(2) A single exit is permitted from a dwelling unit provided the exit is an exterior door at or near ground level and (a) it is not necessary to travel up or down more than 1 storey to reach the exit door, or (b) the uppermost floor level opens to a balcony not more than 6 m above adjacent ground level.

(4) In buildings of residential occupancy not more than 3 storeys in building height, a doorway from a dwelling unit is permitted to open directly into an exit stairway provided such dwelling unit has a second and separate means of egress.

(5) A doorway from a dwelling unit may open onto an interior corridor served by a single exit, or an exterior balcony served by a single exit stairway, or an exterior passageway served by a single exit stairway provided each dwelling unit has a second and separate means of egress.

NBC 1995

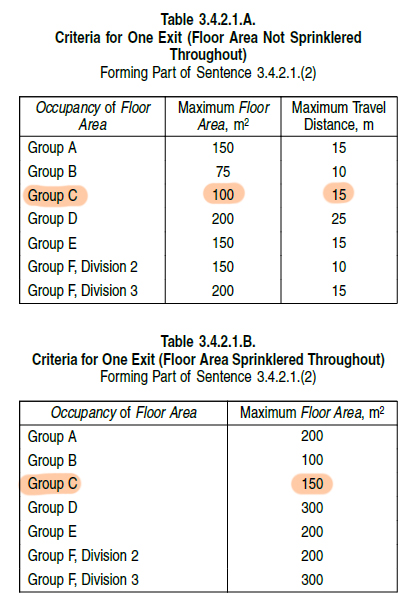

The eleventh edition of the code subdivides the table on Criteria for One Exit between sprinklered and unsprinklered floor areas.

The eleventh edition of the code subdivides the table on Criteria for One Exit between sprinklered and unsprinklered floor areas.

3.4.2. Number and Location of

Exits from Floor Areas

3.4.2.1. Minimum Number of Exits

1) Except as permitted by Sentences (2) to (4), every floor area intended for occupancy shall be served by at least 2 exits.

2) A floor area in a building not more than 2 storeys in building height, is permitted to be served by one exit provided the total occupant load served by the exit is not more than 60, and

a) in a floor area that is not sprinklered throughout, the floor area and the travel distance are not more than the values in Table 3.4.2.1.A., or

b) in a floor area that is sprinklered throughout

3.4.2.1. Minimum Number of Exits

1) Except as permitted by Sentences (2) to (4), every floor area intended for occupancy shall be served by at least 2 exits.

2) A floor area in a building not more than 2 storeys in building height, is permitted to be served by one exit provided the total occupant load served by the exit is not more than 60, and

a) in a floor area that is not sprinklered throughout, the floor area and the travel distance are not more than the values in Table 3.4.2.1.A., or

b) in a floor area that is sprinklered throughout

i) the travel distance is not more than 25 m, and

ii) the floor area is not more than the value in Table 3.4.2.1.B.

NBC 2005

The introduction of objective and functional statements to accomodate performative code compliance.

The introduction of objective and functional statements to accomodate performative code compliance.

Division A - Part 2.2 Objectives

OS1 Fire Safety An objective of this Code is to limit the probability that, as a result of the design or construction of the building, a person in or adjacent to the building will be exposed to an unacceptable risk of injury due to fire. The risks of injury due to fire addressed in this Code are those caused by—

OS3 Safety in Use

An objective of this Code is to limit the probability that, as a result of the design or construction of the building, a person in or adjacent to the building will be exposed to an unacceptable risk of injury due to hazards. The risks of injury due to hazards addressed in this Code are those caused by—

Division A - Part 3.2 Functional Statements

F05 To retard the effects of fire on emergency egress facilities.

F06 To retard the effects of fire on facilities for notification, suppression and emergency response.

F10 To facilitate the timely movement of persons to a safe place in an emergency.

F12 To facilitate emergency response.

OS1 Fire Safety An objective of this Code is to limit the probability that, as a result of the design or construction of the building, a person in or adjacent to the building will be exposed to an unacceptable risk of injury due to fire. The risks of injury due to fire addressed in this Code are those caused by—

OS1.1 – fire or explosion occurring

OS1.2 – fire or explosion impacting areas beyond its point of origin

OS1.3 – collapse of physical elements due to a fire or explosion

OS1.4 – fire safety systems failing to function as expected

OS1.5 – persons being delayed in or impeded from moving to a safe place during a fire emergency

OS3 Safety in Use

An objective of this Code is to limit the probability that, as a result of the design or construction of the building, a person in or adjacent to the building will be exposed to an unacceptable risk of injury due to hazards. The risks of injury due to hazards addressed in this Code are those caused by—

OS3.1 – tripping, slipping, falling, contact, drowning or collision

OS3.2 – contact with hot surfaces or substances

OS3.3 – contact with energized equipment

OS3.4 – exposure to hazardous substances

OS3.5 – exposure to high levels of sound from fire alarm systems

OS3.6 – persons becoming trapped in confined spaces

OS3.7 – persons being delayed in or impeded from moving to a safe place during an emergency (see Appendix A)

Division A - Part 3.2 Functional Statements

F05 To retard the effects of fire on emergency egress facilities.

F06 To retard the effects of fire on facilities for notification, suppression and emergency response.

F10 To facilitate the timely movement of persons to a safe place in an emergency.

F12 To facilitate emergency response.

The original of this code is available for download on the NRC Publications archive:

Sources:

Archer, J.W. (2003). A Brief history of the National Building Code of Canada. Journal of the Ontario Building Officials Association, March, p.24-25.

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=8bff8e43-1abc-4733-b5f7-5750227515cf

National Research Council. (2020). Historical editions of Codes Canada publications (1941-1998).

https://nrc.canada.ca/en/certifications-evaluations-standards/codes-canada/codes-canada-publications/historical-editions-codes-canada-publications-1941-1998

National Research Council Canada. (2020). Canada's national model codes development system.

https://nrc.canada.ca/en/certifications-evaluations-standards/codes-canada/codes-development-process/canadas-national-model-codes-development-system

Breneman, Scott. et al. (2019). Tall Wood Buildings in the 2021 IBC. Woodworks, Wood Products Council.

https://www.woodworks.org/wp-content/uploads/wood_solution_paper-TALL-WOOD.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3Ephq57YljCOP_GNZNkMGoZBOFhtnWLnIJi13OXXOXIM4b9kKSoi0r7Tg

Calder, K et al. (2015). The Historical Development of the Building Size Limits in the National Building Code of Canada. The Canadian Wood Council / Sereca Consulting Inc.

https://cwc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/HistoricalDevelopment-BldgSizeLimits-NBCC-2015-s.pdf

Calder, K et al. (2008). A Historical Perspective on Building Heights and Areas in the British Columbia Building Code (Senez Reed Calder Historical Report).

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/construction-industry/building-codes-and-standards/reports/2008_senez_reed_calder_2008_10_17.pdf