Montreal

An exception in North America, Montreal offers an alternative history of medium-density housing encouraged by the city’s distinct regulations allowing curved and spiral stairs to serve as exits.

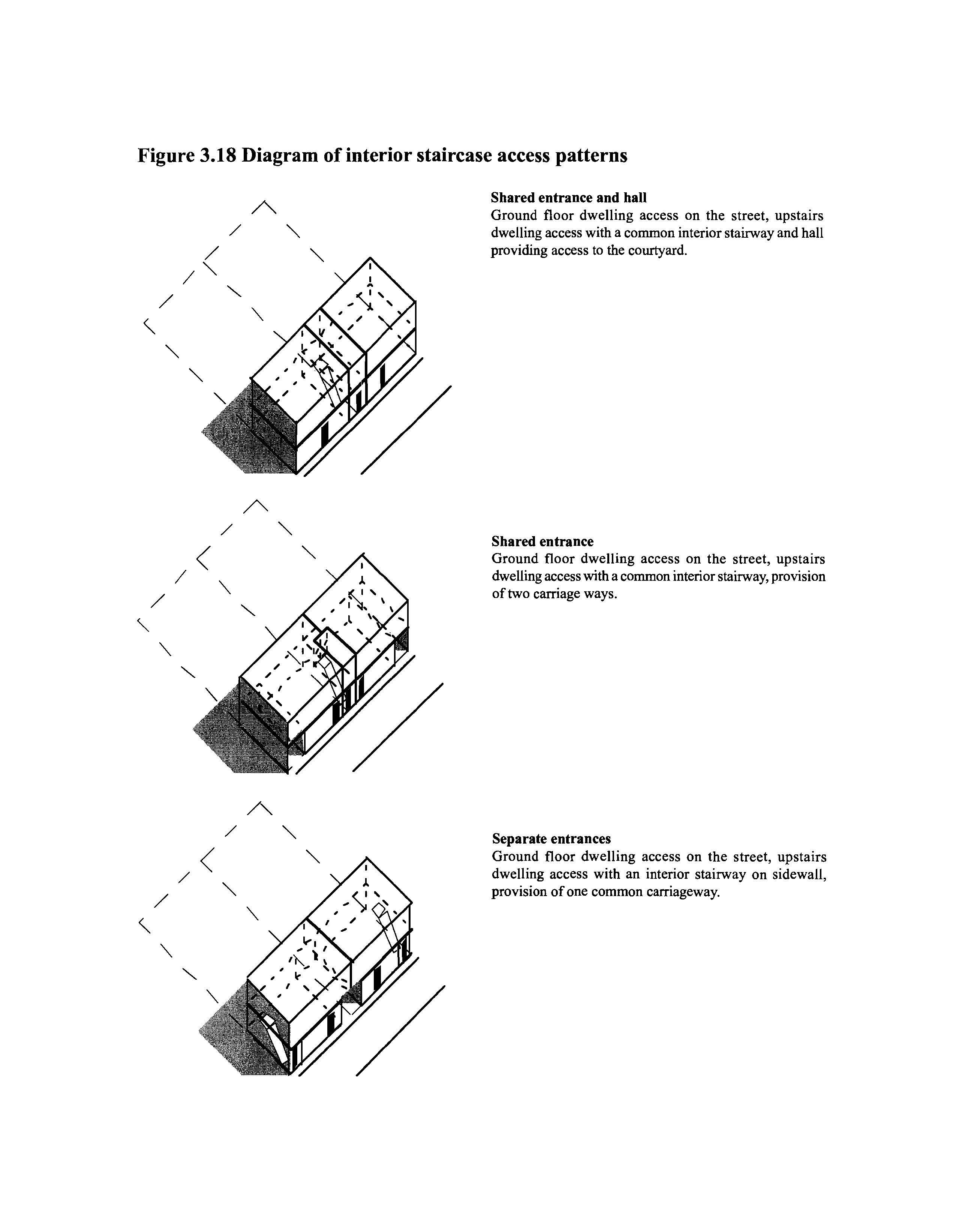

Along with Saint John, Winnipeg, Vancouver, and Lloydminster, Montreal is one of the few chartered cities in Canada with the power to draft municipal bylaws that contravene provincial and federal regulations. The “Montreal Plex” is a form of missing-middle housing made possible by these powers: it consists of three or more stacked dwelling units that share a curved exterior staircase on the front and a spiral stair at the rear of the building. The National Building Code requires any curved or spiral stair that serves more than one dwelling unit to have “an inside radius that is not less than twice the stair width,” which translates to such stairs being so inefficient as a measure of floor area that they are only used for monumental and processional spaces like a theatre or grand entrance. However, Article 29 of Montreal Bylaw 11-018 includes an exception to the National Building Code to allow for tight-radius spiral stairs as a shared exit for two dwelling units per storey in buildings of up to three storeys.The economy of scale that results from this distinction is one of the reasons why Montreal’s density and mix of housing options is so unique within Canada. Modern infill projects, like ‘Les Quatres Arbres’ at 4878 Avenue Henri-Julien in the Plateau neighbourhood, are feasible precisely because of this particular code exception. Anywhere else in Canada - including in Laval and Brossard directly adjacent to Montreal - such designs are not permitted and municipalities do not have the legal authority to create an exception from the provincial code.

CITY OF MONTREAL

BY-LAW 11-018

By-law amending the By-law concerning the construction and conversion of buildings (11-018-3)

BY-LAW 11-018

By-law amending the By-law concerning the construction and conversion of buildings (11-018-3)

Coming into force: 2020-01-23

SUBSECTION IVMEANS OF EGRESS

_______________

29.1. Despite Article 9.8.3.1. of Division B of the Code, exterior stairways that only serve dwelling units and do not constitute their only exit may be curved in whole or in part, under the following conditions:

(1) they serve a level located no more than one storey above the first floor;

(2) they serve no more than 2 dwelling units per storey;

(3) they have equal treads of at least 225 mm, when measured 500 mm from the narrowest end;

(4) the rotation between the two levels is in the same direction.

29.2. Despite Article 9.8.3.1. of Division B of the Code, spiral stairs permitted under sentences (3) or (4) of Article 9.8.4.5. of Division B of the Code, may be curved in whole or in part, where each individual curve turns through an angle of at least 180 degrees.

29.3. Despite Sentence (1) of Article 9.8.2.1. of Division B of the Code, where a dwelling unit has at least 2 means of egress, one of them may be an exterior stairway with a clear width of at least 760 mm, under the following conditions:

(1) the stairway only serves dwelling units;

(2) the stairway serves no more than 2 dwelling units per floor area.

29.4. Despite Sentence (1) of Article 9.8.4.3. of Division B of the Code, winding stairs on an exit stairway serving no more than 2 dwelling units per storey are not required to conform to Article 3.4.6.9. of Division B of the Code, where they meet the following conditions:

(1) they have a tread of at least 150 mm, measured from the narrowest end;

(2) they have a tread of at least 230 mm, measured 300 mm from the narrowest end;

(3) they turn in the same direction.

VILLE DE MONTRÉAL

RÈGLEMENT 11-018-3

RÈGLEMENT 11-018-3

Règlement modifiant le Règlement sur la construction et la transformation de bâtiments (11-018) (11-018-3)

Entrée en vigueur: 2020-01-23

SOUS-SECTION IVMOYENS D’ÉVACUATION

_______________

29.1. Malgré l’article 9.8.3.1. de la division B du Code, un escalier extérieur qui ne dessert que des logements et qui ne constitue pas leur seule issue peut être tournant en totalité ou être tournant en une ou plusieurs parties aux conditions suivantes :

1° il dessert un niveau situé à au plus un étage au-dessus du premier étage;

2° il dessert au plus 2 logements par étage;

3° il comporte des girons égaux d’au moins 225 mm, lorsque mesurés à 500 mm de l’extrémité la plus étroite;

4° la rotation entre 2 niveaux s’effectue dans le même sens.

29.2. Malgré l’article 9.8.3.1. de la division B du Code, un escalier hélicoïdal autorisé en vertu des paragraphes 3 ou 4 de l’article 9.8.4.5. de la division B du Code, peut être tournant en totalité ou être tournant en une ou plusieurs parties lorsque chaque partie tournante permet de tourner d’au moins 180 degrés.

29.3. Malgré le paragraphe 1 de l’article 9.8.2.1. de la division B du Code, lorsqu’un logement comporte au moins 2 moyens d’évacuation, l’un d’eux peut être un escalier extérieur d’une largeur libre minimale de 760 mm, aux conditions suivantes :

1° l’escalier ne dessert que des logements;

2° l’escalier dessert au plus 2 logements par aire de plancher.

29.4. Malgré le paragraphe 1 de l’article 9.8.4.3. de la division B du Code, il n’est pas obligatoire que les marches dansantes d’un escalier d’issue extérieur desservant au plus deux logements par étage soient conformes à l’article 3.4.6.9. de la division B du Code, si elles répondent aux conditions suivantes :

1° elles ont un giron d’au moins 150 mm mesuré au point le plus étroit;

2° elles ont un giron d’au moins 230 mm mesuré à 300 mm du point le plus étroit; 3° elles tournent dans la même direction.

Recent Spiral Stair Projects in Montreal

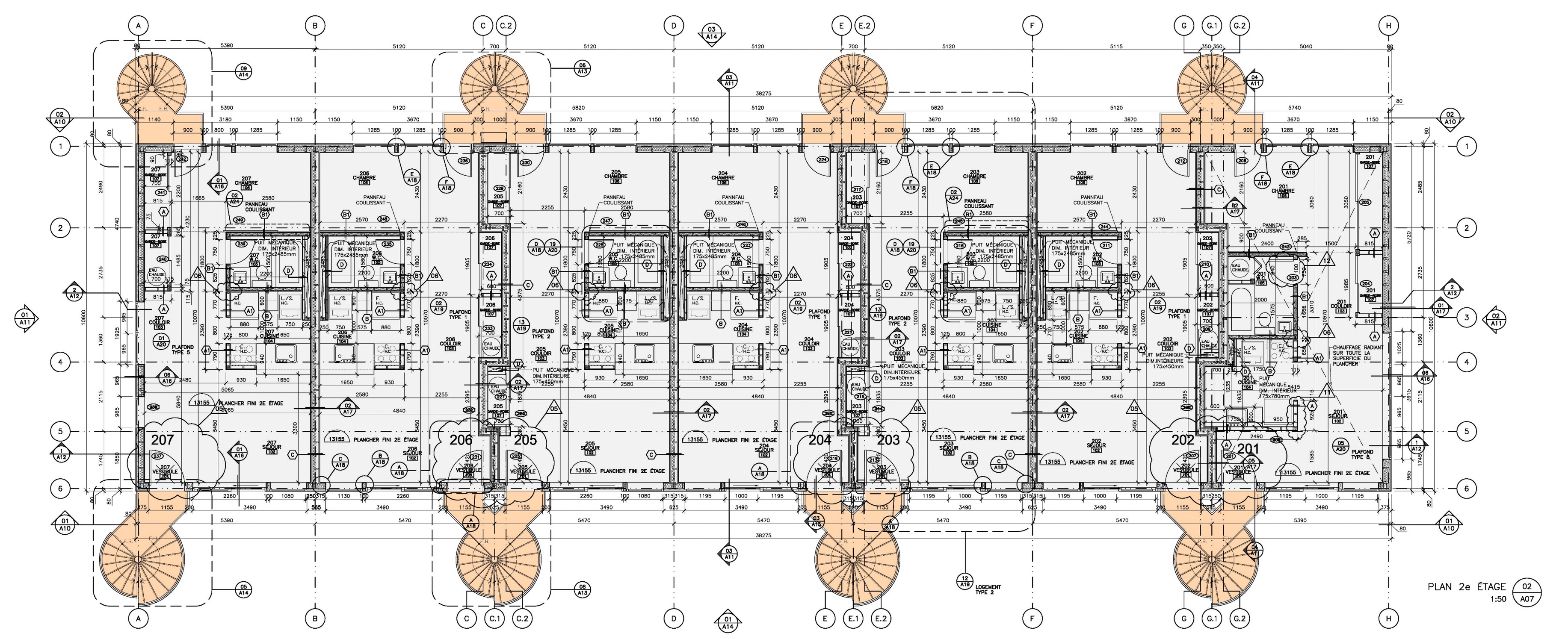

Les Quatre Arbres

Atelier Raouf Boutros Architect (2009)4878 Rue Henri-Julien, Montreal, QC

Height: 3 storeys

Use: 20 dwelling units

Floor Area: 1100m2

Construction: Protected Wood Frame

Stair: Exterior Spiral Stair (Steel Frame with Wood Guard)

Sprinklered: No

The special conditions of the Montreal By-law allow for these exterior spiral stairs to serve as exits. This project was designed with a spiral stair at the front and back of each unit, serving the maximum of two dwelling units on the second and third storey.

Habitations Saint-Michel Nord

Saia Barbarese Toupouzanov Architectes (2020)8550 Allée Léo-Bricault, Montreal, QC

Height: 3 storeys

Construction: Protected Wood Frame

Stair: Exterior Spiral Stair (Steel Frame with Metal Guard)

Sprinklered: No

This housing project is configured with an interior exit stair accessed from the main entrance and an exterior spiral stair as second means of egress for the second and third storey units.

Images Copyright James Brittain. Source ArchDaily.

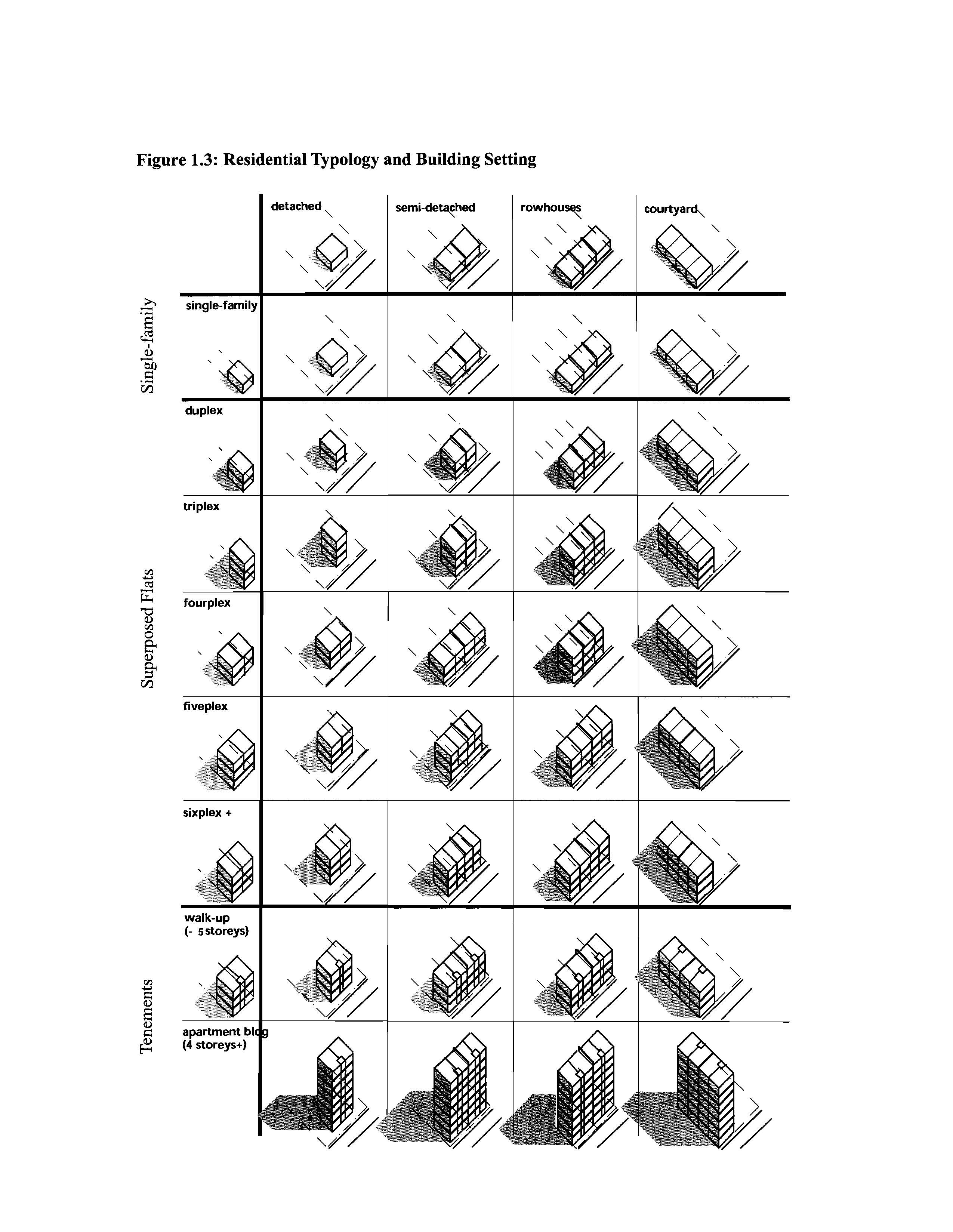

“By the turn of the century, Montreal’s working-class neighbourhoods had developed a distinctive housing form known as the ‘superposed’ flat. These were two or more commonly, three-storey structures, with an apartment on each floor, exterior staircases, and balconies both at the front and the back. In areas like the Plateau, the superposed flats not only created an unusually dense urban form but provided owners with an opportunity to live on one floor and generate welcome additional income by renting out the others. ‘In the nineteenth century’, according to a CMHC study on Montreal’s housing, ‘the appeal of real estate ownership resided in the potential rental income, rather than the propriety of one household to own its own dwelling.’ This model, which acknowledges the high carrying costs of urban houses, was also common in cities like Philadelphia and Glasgow, and continues to find currency in the guise of basement apartments and secondary suites.”

- John Lorinc, excerpt from “Housed Divided:

How the Missing Middle can Solve Toronto’s Affordability Crisis”

- John Lorinc, excerpt from “Housed Divided:

How the Missing Middle can Solve Toronto’s Affordability Crisis”

“In the urban arena, rarely have architectural historians dared tread very far into the reaches of the urban vernacular, such that noteworthy works by Eric Arthur on Toronto or Jean-Claude Marsan on Montreal, while granting some recognition to the existence of an urban vernacular tradition, have done so only fleetingly. Other architectural historians who have attempted to focus exclusively on the subject of the urban vernacular, such as Stefan Muthesius and the English terraced house or Lucie K. Morisset, on Arvida, are of a fairly new breed and stand out as unusual. More typical are works like Norbert Schoenauer who, in a massive life-consuming investigation of urban housing, seems to have missed entirely the existence of rich traditions of superposed flats in Scotland, France, Italy and the United States, to name but a few countries. Having spent the better part of his career in Montreal, he felt the need to at least acknowledge their existence, devoting one page to the genre out of an opus of 500, and dismissing it as a mere regional peculiarity. Apparently, one is left to conclude that urban housing historically is made up of single-family housing and apartment buildings!

The same blind spot towards superposed flats crops up in virtually all the architectural guides to individual cities in North America. The American Institute of Architects' Guide to Chicago is symptomatic of the tendency. Despite having North America's largest volume of two-flat and three-flat housing both historically and today, the architectural historians selected only eleven such sites out of a total of 1527 sites covered in the guide, excluding the central business district. Of course the guide is full of single-family houses, even very modest ones, and none of the eleven superposed flats are discussed in any depth, almost as though they were of little meaning. Other cities where superposed flats are common (e.g. Boston, Richmond, St. Louis to name but a few) have not even been that lucky in their architectural guidebooks.

How does such a systematic blind spot arise? Perhaps the obsession with single-family housing in twentieth-century North America has conditioned researchers to ignore other forms of housing, excepting, of course, apartment buildings because of their sheer bulk and the fact that they tend to be architect designed. Perhaps also superposed flats are seen superficially as merely single-family type houses which have been divided into two or three flats, ignoring the fact that they are a house type of their own. Clearly what has been missed are the deep cultural and historical roots of such housing and their powerful significance in terms of generating eminently habitable low-cost housing in dense yet human-scaled neighbourhoods.”

Sources:

Alter, Lloyd. (2018). Why Did Montreal Get Those Twisty Deathtrap Stairs?. Treehugger.

https://www.treehugger.com/why-did-montreal-get-those-twisty-deathtrap-stairs-4857509

Kennedy, A. (2002). Montreal's Duplexes and Triplexes. McGill, The Fifth Column, 64-69.

https://fifthcolumn.mcgill.ca/article/view/645/633

Hanna, D. and Dufaux, F. (2002). Montreal: A Rich Tradition in Medium Density Housing. CMHC.

https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/schl-cmhc/nh18-1-2/NH18-1-2-37-2002-eng.pdf

Oh The Urbanity!. (2021). Five Dense "Missing Middle" Neighbourhoods in Montreal. YouTube video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mYCAVmKzX10&ab_channel=OhTheUrbanity%21

Urban kchoze. (2014). Les escaliers de Montréal vs towers of Toronto. Blogspot.

https://urbankchoze.blogspot.com/2014/04/les-escaliers-de-montreal-vs-towers-of.html

Urban kchoze. (2017). A catalog of density (Quebec/Canada version). Blogspot.

http://urbankchoze.blogspot.com/2017/03/a-catalog-of-density-quebeccanada.html