Code Change Request

Original submissions to Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC) in April 2022

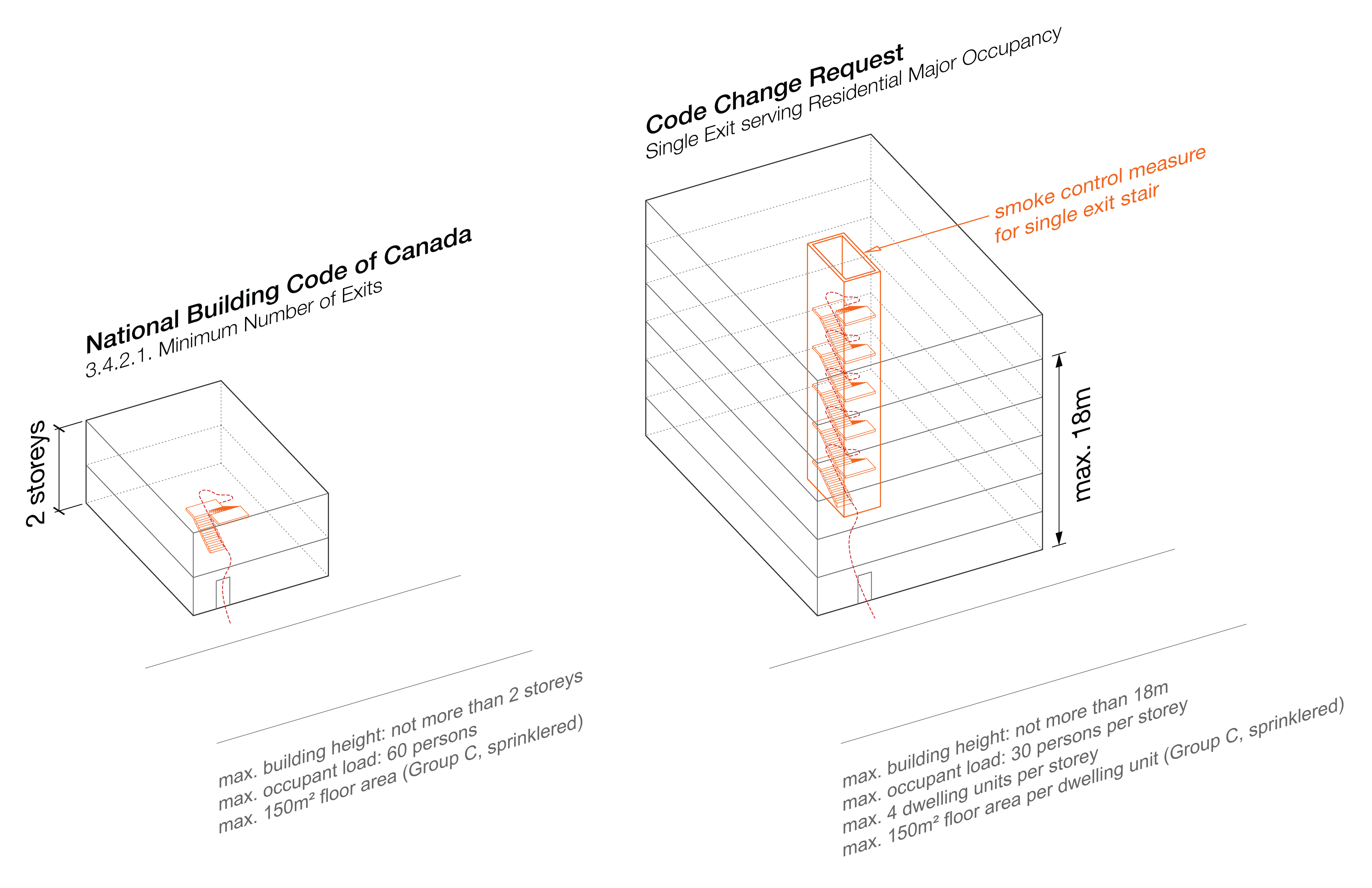

CCR 1816

Part 3 – Single egress for multi-unit residential buildings up to 18m in height

CCR 1815

Part 9 – Single egress for multi-unit residential buildings up to 3 storeys

Proponent

Conrad Speckert,

LGA Architectural Partners

Submitted

2022-04-18 (resubmitted 2025-03-08)

Code Reference(s)

NBC Div. B – 3.4.2.1

NBC Div. B – 9.9.8.2

What is the problem?

The requirement for two means of egress in multi-unit residential buildings exceeding two storeys may be an outdated condition of pre-modern fire safety practices in combustible construction. The National Building Code of Canada is inconsistent with (and does not allow for the same design flexibility as) building codes in other jurisdictions and fails to recognize that a second egress may be unnecessary for “missing middle” and mid-rise housing typologies where other life safety measures are provided.

By prohibiting single egress designs at this scale, the National Building Code limits the feasibility of buildings that are between low-rise single-family homes and high-rise apartment buildings. Making it difficult to build mid-rise housing prevents urban areas from developing more sustainable growth and increasing the balanced supply of housing with an expanded range of affordable options.

This code change request recognizes that the requirement for two means of egress is appropriate for larger buildings and non-residential occupancies. However, requiring a second egress is a prohibitive burden for smaller multi-unit residential projects, whereas one exit is permitted in many other jurisdictions.

Note: The supporting documentation includes a jurisdictional scan of other building codes.

This code change request falls within several of the CCBFC’s strategic technical and policy priorities as a select fire and life safety topic and as a targeted topic. Accessibility is also addressed in terms of egressibility, the proposed life safety measures improve the protection and fire safety for disabled occupants remaining in their suite during an emergency.

Single egress also indirectly addresses the priorities of climate change mitigation and adaptation, and energy-efficiency, given the improved building form factor, design flexibility for passive ventilation and daylighting, and the sustainable urban development benefit of single stair buildings. This CCR also relates to the priority of alterations to existing buildings in future code editions, for instance, as an opportunity for a five-storey apartment building with additional structural capacity to construct a sixth-storey addition, provided the limitations and life safety measures of the requested change are met.

Requested Change

Please email conrad.speckert@mail.mcgill.ca to request a copy of the original code change requests and resubmission documents.

Impact Analysis: What are the cost/benefit implications?

The benefits in efficiency, cost and improved livability for a single egress building significantly outweigh the cost of the additional life safety measures. The requested change offers the measurable benefit of increased floor area efficiency and reduced hard construction costs for “missing middle” and mid-rise housing types, as well as making such buildings feasible on smaller properties.The requested change also has additional benefits for the environmental, spatial, and social quality of multi-unit residential buildings, such benefits include:

- making it easier for dwelling units to receive natural daylight from both sides as “through units”,

- allowing for cross-ventilated dwelling units rather than the deep, single-orientation layouts typical of double-loaded corridor buildings requiring two means of egress,

- balancing the exposure of each dwelling unit to urban and traffic noise, such that bedrooms can be placed on the quiet side and living areas along the street facing side of the building,

- making it easier to design larger, family-oriented dwelling units with three to four bedrooms, and

- improving the sense of community and social interaction in an apartment building by decreasing the number of dwelling units sharing an exit.

The requested change does not result in additional costs compared to buildings adhering to the existing acceptable solutions requirement for two means of egress. The requested change enables the alternative of a single stair design, with limitations on the building size and requirements for additional life safety measures to compensate for providing one exit. This additional design flexibility may be cost neutral or, in some cases, lead to cost savings. It may also bring buildings back into feasibility on smaller sites where the lot size does not accommodate a design complying with the second egress requirement.

What are the enforcement implications?

The requested change can be enforced within the current enforcement framework of design review and permit approvals, as well as the administrative requirements for evacuation plans.

Other Comments

This code change request is being submitted in response to the official correspondence on March 31, 2022, from the Ontario MMAH (Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing) requesting the CCBFC to prioritize a code change to allow for “a single means of egress in some residential buildings as a Building Code change that could enable the construction of more gentle density and multi-unit housing.”

In January 2022, several architects, planners and developers co-signed a letter sent to the Ontario Housing Affordability Task Force recommending a building code change to “permit residential buildings of up to six storeys with a single exit stair” with additional life safety measures.

Since the original submission of the CCR in April 2022, several US and Canadian jurisdictions have initiated studies and changes to address single exit stair (SES) building design. Several architects and building code consultants across Canada have also developed alternative solution proposals for small multi-unit residential buildings served by a single exit stair for up to 3 to 6 storeys in height.

The proponent is willing to provide a presentation and is willing to provide additional supporting documentation and information.

Supporting Documentation

- “Small Single-Stairway Apartment Buildings

Have Strong Safety Record.” Pew Trust. February 27, 2025.

-

“Potential to Update the Vancouver Building

Bylaw to Enable Single Egress Stairs.” City of Vancouver. February 26, 2025

-

“The Seattle Special: A US City’s Unique

Approach to Small Infill Lots.” Mercatus Center. December 2, 2024.

-

“Legalizing Mid-Rise Single-Stair Housing

in Massachusetts.” Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University.

October 10, 2024.

-

NFPA Single Exit Stair Symposium.

(Various

articles, reports and presentations).

-

“Housing Solutions Lost in Translation

without a National Fire Administration.” CAFC. August 2024.

-

“Evaluating Stakeholder Concerns About

Proposed Single Egress Stairs.” University of the Fraser Valley. July 2024.

-

“Single Exit Stair: Ontario Building Code

Feasibility Study”. LMDG Building Code Consultants. July 2024

-

“Single Egress Stair Building Designs:

Policy and Technical Options Report, British Columbia.” Jensen Hughes. June

2024.

-

“Point Access Block Building Design:

Options for Building More Single-Stair Apartment Buildings in North America.” Cityscape.

March 2024.

-

“BC Housing Single Stair Report.” PUBLIC

Architecture. February 2024

-

“OAFC Position on Single Exits in

Buildings up to Six Stories or that Exceed Current Code Requirements.” OAFC.

January 9, 2024.

-

Jurisdictional

Scan: Maximum Allowable Building Height with Single Egress for Multi-Unit

Residential Occupancies. April 2022. Prepared by proponent. (refer to most recent version at www.secondegress.ca)

-

Case Study Plans:

Examples of Single

Exit Stair Multi-unit Residential Buildings in other Jurisdictions. April 2022. Prepared

by proponent.

-

“Ontario MMAH – Single Egress.”

Correspondence with CCBFC.

March 31, 2022.

- “Re: Building Code Change to Enable Single Stair Residential Buildings up to Six Storeys.” Letter to the Ontario Housing Affordability Task Force. January 27, 2022.

References (included with original submission in April 2022)

-

Booth, R.

(2022). “Rethink for skyscraper near Grenfell site with single fire escape

staircase.” The Guardian.

-

Bukowski, R. and Kuligowski, E. (2004),

The Basis for Egress

Provisions in U.S. Building Codes, Interflam.

-

Bukowski, R.

(2009). Emergency Egress from Buildings. NIST Technical Note 1623. U.S.

Department of Commerce: National Institute of Standards and Technology.

-

Calder, K. et al. (2015).

The Historical Development of the Building Size Limits in the National Building

Code of Canada. The Canadian Wood Council / Sereca Consulting Inc.

-

Calder, K.,

and Senez, P. (2016). The Key Modes of Fire Spread in Wood-Framed Apartment

Buildings – A Canadian Perspective. World Conference on Timber Engineering.

-

Clare, J. and

Kelly, H. (2017). Fire and at risk populations in Canada - Analysis of the

Canadian National Fire Information Database.

-

Eliason, M.

(2021). “The Case for More Single Stair Buildings in the US,” Treehugger

Magazine

-

Eliason, M.

(2021). “Seattle’s Lead on Single Stair Buildings.” The Urbanist.

-

Eliason, M.

(2021). “Unlocking livable, resilient, decarbonized housing with Point Access

Blocks,” City of Vancouver.

-

FEMA. (2011). Fire Death Rate Trends: An

International Perspective. U.S. Fire Administration National Fire Data Center,

Topical Fire Report Series, Vol 12, Issue 8.

-

Garis, L.,

Clare, J. (2016). “Life Safety Systems, Fire Department Intervention, and

Residential Fire Outcomes. Analysis of 28 Years of BC Fire Incident Reports:

1988-2015.” University of the Fraser Valley, Centre for Public Safety and

Criminal Justice Research.

-

Garis, L. et al.

(2018). “Sprinkler Systems and Residential Structure Fires – Revisited:

Exploring the Impact of Sprinklers for Life Safety and Fire Spread.” University

of the Fraser Valley, Centre for Public Safety and Criminal Justice Research.

-

Garis, L. et

al. (2019). “Fire Protection System(s) Performance in the Residential Building

Environment: Examining the Relationship between Civilian and Firefighter

Injuries: A Retrospective Evaluation of Residential and Residential Apartment

Fires, 2005 to 2015.” University of the Fraser Valley, Centre for Public Safety

and Criminal Justice Research.

-

Garis, L.,

Clare. J. (2020). “Is taller safer? A closer look at the impact of building

height and life safety systems.” Firefighting in Canada.

-

Grabar, H.

(2021). “The Single-Staircase Radicals Have a Good Point,” Slate Magazine.

-

HM Government. (2006). Fire Safety Risk

Assessment: Sleeping Accomodation.

-

Proulx, G.

(2001). Occupant Behaviour and Evacuation. NRC Publications Archive.

NRCC-44983.

-

Ontario

Association of Architects. (2019). Housing Affordability in Growing Urban

Areas. SvN Architects + Planners.

-

Royal Institute

of British Architects. (2022). RIBA fire safety policy note – February 2022.

-

Senez, P. et al. (2008). A Historical

Perspective on Building Heights and Areas in the British Columbia Building Code

(Senez Reed Calder Historical Report).

-

Stock, B.,

Wallasch, K. (2020). Fire Safety Requirements for High-Rise Residential Towers

in England and Germany. FeuerTrutz

International 2020.

-

Stock, B., Wallasch,

K. (2009). Single

living. Fire & Risk Management

(F&RM) Journal, 19.

-

Winberg, D. (2016). International Fire Death Rate

Trends. SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden.

-

Wu, S. (2001). The Fire Safety Design of

Apartment Buildings. Fire Engineering Research Report 01/10. University of

Canterbury School of Engineering.

-

Zheng, A. et al. (2022). Fire Severity Outcome Comparison of Apartment Buildings

Constructed from Combustible and Non-combustible Materials. University of the

Fraser Valley, Centre for Public Safety and Criminal Justice Research.

-

Zimmerman, F.

(2010). Breaking Up with the Double Loaded Corridor: A Study of Progressive

Housing Design and it’s Influence on Social Networks.

This website, including all data and information incorporated herein, is being provided for information purposes only. For certainty, the author provides no representation or warranty regarding any use of or reliance upon this website, including no representation or warranty that any architectural designs comply with applicable laws including any applicable building code requirements or municipal by-laws. Any use of or reliance upon this website by any person for any purpose shall be at such person’s sole risk and the author shall have no liability or responsibility for any such use of or reliance upon this website by any person for any purpose. Prior to any use of or reliance upon this website by any person for any purpose, consultation with a professional architect duly licensed in the applicable jurisdiction is strongly recommended.